Tim Stafford

Cities of Refuge

The migrant crisis.Consumers of mainstream news can be forgiven for believing that Germany is awash in refugees. The truth is that they are seldom seen on German streets, and that most Germans go about their lives without ever meeting a refugee.

The refugees are there—1.2 million entered Germany last year—but they are out of sight, in what Germans infelicitously call "camps." On my first day in Germany I stand in lightly falling snow with Ricarda Wallmeyer, a passionate refugee advocate, at the Tempelhof refugee camp. Tempelhof was Berlin's airport through the Nazi era, and it retains a movie-set ambiance of massive stone buildings decorated with carved war eagles. One almost expects Joseph Goebbels to drive by in an open Mercedes. Wallmeyer, who escaped from East Germany as a child, tells me that her most dreadful moment volunteering with the refugees was when she was told to lead a queue of about a hundred to the showers. They obediently followed but she was in tears, thinking of other processions in another era.

Berlin: Refugee advocate Ricarda Wallmeyer.

The government has commandeered Tempelhof to house refugees. Thousands are put up in its massive airplane hangars, partitioned into living spaces. I cannot get to them, however, for the complex is tightly guarded and no one can enter except on official business. Refugees are free to come and go, but they are invisible in the cold and snow of a quiet neighborhood.

Camps are everywhere in Germany—in gymnasiums, converted office buildings, apartment complexes, warehouses and army bases, or in new-made complexes of adapted shipping containers or army tents. Every city has multiple sites, closely guarded. The security is intended to protect refugees (and perhaps, also, government officials) but its impact is to cut off the refugees from ordinary Germans.

Take, for example, the Pakistani I will call Hassan Goraya, whom I interview in the lobby of a converted office building still adorned with bright signs from a Swedish firm. Hassan has dark, tight skin molded to the contours of his face; he is bone-thin, with a worried expression and a charming smile. We go through a lengthy wrangle with the security guards over whether we can sit in the building's shabby lobby to talk. They have to call a superior officer before they will grant Goraya such freedom.

Goraya, who worked in quality assurance for a medical instrument company in Pakistan, tells a harrowing tale of escape from a mafia-like clan running a protection racket. He says they kidnapped him, demanded ransom in the hundreds of thousands of dollars, and (when the money wasn't forthcoming) threw him from a moving car. (He shows me scars on his face and wrist.) To escape from escalating death threats, he paid smugglers $2,000 to get him to Turkey. He was shot at on the border of Turkey and Iran, ran through the mountains in the dead of night, and reached Istanbul in May of 2015, just before the height of the migration surge. Goraya paid another $800 to get across the Aegean Sea to Greece, and arrived in Berlin at midnight, September 8, near the height of the extraordinary summer crush.

Goraya smiles gratefully when he thinks of the generosity he's encountered in Germany—he remembers the welcome banners at the Munich train station—yet he seems utterly isolated. When I ask him his reaction to the New Year's Eve assaults in Cologne, when gangs of young male immigrants assaulted German women, he has no idea what I am talking about. He sees no news, speaks no German, and appears to have no friends. For almost six months he has tried to get the government interview that would begin his process of seeking asylum. He regularly lines up in an overnight queue, like someone seeking tickets for a rock concert. Those first in line can get in to see an official in the morning. But so far, all Goraya gets is an appointment to come again; and he must again stand in line all night, sometimes in a rainstorm. He has no idea whether he will ever get refugee status. He may well be expelled back to Pakistan. In the meantime all he can do is sleep all day, and wait.

One can only guess—the German bureaucracy is "less than perfectly transparent," as one pastor puts it to me—but Goraya's case is probably borderline. By law Germany is obliged to offer asylum to all those experiencing "persecution or a well-founded fear of persecution on account of race, religion, nationality, membership in a particular social group, or political opinion." Goraya has been persecuted by a criminal gang. Most probably that criminal gang has ties to powerful political figures. But is that the basis of a claim to asylum?

The next night I visit the all-night queue. In Berlin a single government office known as LaGeso handles all official refugee business. Already at 6:00 in the evening I see people converging on the office: dark-skinned men wrapped in warm winter coats; women with heavy garments and headscarves, sometimes carrying children. The night is cold with flurries of rain. In a muddy space in front of the main office are large white tents, like those used as temporary buildings for county fairs. Outside the tents a tense line, almost entirely men, snakes through steel crowd-control barriers, squeezing each other forward. Occasionally I hear a disruption, with loud shouts of protest from the waiting men, and equally vociferous cries from the security guards who keep control. Slowly, a few at a time, the men are allowed into the tents, which are heated. They have a long night of waiting ahead.

Indeed, refugees in Germany do a great deal of waiting. Somebody gives me a diagram, "How to Become a German," that shows the bureaucratic process, as complicated as an electrical schematic. The system has its own sense of order, which at the moment is overwhelmed by huge numbers and the extraordinary task of making sense of a case like Goraya's.

Berlin : Pro-refugee march around the Templehof Airport. Since September 2015 Templehof has been used as an emergency refugee camp.

It is late January, and I am traveling with photographer Gary Gnidovic, following the route of the refugees through Europe, but backwards—from Germany, where nearly all refugees aim to arrive, back through Austria, Croatia, Serbia, and finally Greece. Our goal is not to ponder political solutions but to witness what is happening on the ground. We want to talk with refugees and hear their stories; we want to see what their conditions are like, meet those who are helping them, and take the temperature of the countries along the route. Of course this can change very quickly, as it did after New Year's Eve.

Refugees come from many countries—not just Syria, the epicenter of war, but also Iraq, Afghanistan, Iran, Pakistan, Libya, Yemen, Somalia. Tarek, whom I meet in a pizza restaurant on our second day in Berlin, is as different from Goraya as can be. He comes from Aleppo, Syria, and wears a customized t-shirt that he got that day from six German friends who share his birthday. The shirt says "Peace" in Arabic. With his light skin, his short beard, and his stocking cap, Tarek could pass for a German. He is writing a play to be performed by refugees; he is a singer who shows me a video on his phone of his most recent performance singing Coldplay in a church, in front of a huge cross. Having won his refugee status two months before, after eight months of waiting, he has a job cleaning apartments and looks forward to starting school. (He finished high school in Syria.) "I really respect this country," he says. "They are not treating us like criminals. I feel safe here. Many people want to help."

Yet stress recently made him drop out of school. He thinks constantly of his family. He has a wife and a son (whom he has never seen) in Turkey, and he is not altogether confident that he will ever get permission for them to join him in Germany. Three married sisters remain in Aleppo, their lives at risk. Tarek comes from an educated, middle-class family. One brother is a dentist, another graduated with a degree in electrical engineering, both parents worked for the Syrian government. He is proud of his Syrian culture, which he sees as creative and welcoming. But "there is no Syria any more."

Tarek says that many friends died or disappeared in the anti-government protests that kicked off the civil war. He was working in Qatar, so isolated and anxious he was unable to function. He flew to Turkey, where his parents, his fiancée, and several siblings joined him. For a time Tarek produced and sold olive-oil soap in Istanbul. He married his fiancée, who was soon pregnant. Ironically, this was the impetus for him to try to reach Europe. He saw no future for his family in Turkey, where he could not legally work.

The journey he describes to me began with a smuggler leading him and four others across the Turkish border into Bulgarian forests. A series of cheating smugglers led to repeated arrests and mistreatments by border guards. He was beaten by Bulgarian police and shackled to a wall, standing, for 24 hours. He paid smugglers thousands of dollars to reach Germany.

Tarek comes across as articulate, forthright, and capable. Culturally, he seems likely to fit well into German society. Still, his anxiety leaks out at times, especially when he talks about his future (as yet unknown) and his family.

(Since our trip, I have heard from Wallmeyer that Tarek returned to Turkey to try to bring his wife and son to Germany. Failing to get the proper papers, some of which must come from Syria, he is considering using smugglers to get his family to Greece. Wallmeyer is urging against that; he might be arrested for trafficking.)

In Hamburg, a short train ride from Berlin, I meet Glen Ganz, a German who grew up in Latin America and now works with refugees on behalf of the German Evangelical Free Church. Ganz presides over the Why Not? Café, a gathering place where refugees come for German classes and a wide variety of other volunteer-led events. Here they meet German society; here they can learn about Jesus. Ganz hopes to start 100 Why Not? Cafes in churches throughout Germany.

For Ganz, it's the opportunity of a lifetime. "This is the biggest migration in human history," he tells me. "If you believe that God made the world, and rules the world, you have to pay attention to what goes on. This is a sign of the time."

Ganz is often frustrated by unimaginative church leadership, and believes that immigration is God's response. "It's not a gift, it's a challenge. We decide if it is a gift. We need to open ourselves to other people. Society in Germany needs to learn to believe again."

I encounter a similar entrepreneurial spirit in Jochen Weise, who is working on a project to take over an abandoned Lutheran church and convert it into a multi-functional community center, complete with start-up companies offering job training, a museum of religious freedom, stores, a fitness center, a church and a school. Weise believes that Germany has entered a third phase of reaction—beyond astonishment and then welcome—in which people are asking how they can integrate refugees into German society. "This is where the church starts," he says.

That sentiment is echoed by pastor Uwe Kloter, whose small Hamburg church has launched a weekly coffee hour welcoming refugees from nearby camps. "I've learned a lot about my church," he says. "I see a lot of fear." But in the house of God, where God reigns, there should be no fear: "The challenge of the refugees is to help us to come back to the love of Christ again." Kloter notes that Chancellor Angela Merkel "is not very popular with the slogan, 'Yes, we can.'" (Merkel, the daughter of a Lutheran pastor, chose to embrace the flood of refugees.) "But I think we can."

Others are less confident. I visit Steffan Schumann, whose third child Noah was born with severe handicaps ten years ago. Schumann quit his job as an economist and launched a remarkable facility, Kupferhof, offering respite to the parents of disabled children. In other words, he is a man with a deep commitment to caring for the weak, and a willingness to take risks to do so. Yet he is offended by the black-and-white presentation of the immigration issue: "Either you welcome them, or you're a Nazi." He thinks a quiet resentment is building that will show itself in the next elections. "Merkel is finished," he predicts.

Berlin: Tarek is from Aleppo, Syria. He’s writing a play to be preformed by refugees.

I expected to find a widespread immigration backlash after the New Year's Eve assaults in Cologne. What I find instead are people like Schumann who worry that Germany has taken on more than it can handle. "It's a world problem," he says. "Why is it just us Germans?"

Schumann takes me to see a camp in his neighborhood, an affluent suburb with horse stables and beautiful older homes. Army tents encircled with wire fencing were plunked down on a playing field in August. "People say they went on holiday and when they came back it was there." There was no notice or consultation. Germans seem to trust their government to an extent unimaginable in America, but the widespread intrusion of refugee camps does raise an alarm.

It seems to me that the tight security around refugee camps works against the larger goal of integrating refugees into German society. This is reinforced when we visit a camp near Klotter's church where security is inexplicably lax. As we stroll through rows of metal containers repurposed for housing, we strike up conversations with friendly Syrians living there. Mohammed immediately invites me into his 20'x8' container for a cup of coffee. While his wife struggles to heat water and his two children stare, Mohammed talks about his decision to leave Damascus. He and his wife were both school teachers until war drove them to Turkey, then on to Greece and finally to Germany.

Their living quarters contain two single beds and a dorm-size refrigerator. Yet it is obvious that, having nothing, they are proud to welcome me into their home. I saw much the same with Hassan Goraya, who brought out nuts and dried fruits to share with his visitors as we sat in the dingy lobby of his camp. To share hospitality, not just to receive it, is part of integration into society.

Munich is a different world from the north-German cities: brash, comfortable, and—judging by skin-tone on the street—far more affected by immigration.

In the late summer and early fall of 2015, Munich's train station was overrun by immigrants. Today the station is back to normal, though numerous kebab joints on nearby streets tell the tale of earlier waves of immigration. In one such establishment I sit with four young Syrian men, joking and laughing through a long afternoon of telling stories.

Munich: Ahmad Abbas from Homs, Syria. In the early part of Syrian civil war, his home was bombed. He and his sister were left unconscious and burned over 70% of their bodies. Thanks to a Western journalist, they were taken to Munich where they were given treatment.

Ahmad Abbas, with glossy black hair flowing over his collar, claims to be the first Syrian to arrive in Germany as a result of the civil war. Asleep in his family home when it was blown up by a tank shell, he was taken to a Free Syrian Army clinic and then to Beirut. Horribly burned, he was photographed by a German journalist, whose extraordinary pictures attracted attention. Charitable organizations flew Abbas to Munich, where he was kept in an induced coma for six weeks. He finally awoke like a character in a fairy tale, having gone to sleep in Syria and awakened in Germany.

The day we meet is his 21st birthday; he will celebrate by visiting the doctors and nurses who saved his life. At the hospital, his friends and supporters crowd around him. Abbas is entering a three-year apprenticeship to become a nurse.

His friend Khaled Alhussein has a Duck-Dynasty black beard and a mischievous smile. When I ask why he left Syria he says his parents insisted on it, because they knew if he stayed in Syria he would have to fight for one army or another. His father somehow got him a passport and put him on a plane to Algeria; from there smugglers carried him by car to Libya and put him on a 60-foot wooden boat carrying 404 people. They were on the Mediterranean for five days before the overloaded engine stopped. Having no engineer on board, they drifted until rescued by the Italian navy. Alhussein made his way to Germany where, after living nine months in various camps, he was accepted as a refugee. Before leaving Syria he had done three semesters of university training in mechanical design; he is now doing an apprenticeship with a hydraulic company.

Mohammed Nasir, 24, studied English literature at Ebla University. He participated in protest marches against an increasingly violent government response. "Many of my friends were killed"—over 100 whose names he recognized, including several first cousins.

When the opposition began to fight back against Assad's army, Mohammed and his entire extended family fled their home in Deir ez-Zur for a small town controlled by the Free Syrian Army. There he and his younger brother Ameen began to work for Global Communities, a humanitarian organization run from over the Turkish border. Once a month the brothers traveled into Turkey to file reports on their research into refugee conditions. It was while they were on such a trip that ISIS forces took control of the town where they were living. ISIS caught and killed two of their friends, one by beheading.

Unable to return to Syria, Mohammed and Ameen stayed eight months in Turkey unsuccessfully seeking legal immigration. Mohammed found work doing IT; Ameen worked temporarily for a Syrian radio station. There were a quarter million refugees in Urfa, the Turkish city where they found refuge.

For months they argued about fleeing to Europe. Mohammed was reluctant; Ameen pushed him to go, and so did their mother. Fearful her sons would be murdered by ISIS, she came over the border carrying her gold jewelry and sold it to fund the journey. When Mohammed received a death threat from ISIS through his Facebook account, he decided that the time had come.

For 2,000 euros each, a small boat carried them in the dead of night to the Greek island of Symi. Swimmers on the beach welcomed them and gave them water to drink. "People were very kind."

The brothers reached Athens by ferry—an astonishingly beautiful trip, says Mohammed, who had never been on the sea—and began to search for another smuggler. This one wanted $5,600 to get them to Belgrade in Serbia.

Rather than pay a smuggler directly, they deposited money with a money handler who gave them a secret password. Only after they had safely arrived at their destination would they telephone to release the money to the smuggler.

In this case, the smuggler proved a cheat. From the Macedonian border he took a group of about 30 refugees wandering through the forest for three days in the rain. Ameen got sick. Wet, cold, and hungry, he said he couldn't stand any more. With eight others from the group the brothers slipped away and found a remote village. Mohammed, who speaks some Russian, was able to communicate that they needed the police. "There are no police here," the villagers said, but they offered food and a place to sleep. In the morning, a knock came at the door. Someone offered to drive the refugees to Scopje, the Macedonian capital, for pay.

Their troubles had only begun. They found another smuggler to take them on to Belgrade. After a long walk over the border into Serbia, he left them, saying he was going to get a car. Instead, the police arrived, and treated them roughly. When Mohammed told them not to put their hands on the children, and to stop waving guns in their faces, the police threatened him. In a moment's confusion he switched jackets with Ameen. The police, to whom perhaps all refugees look alike, took Ameen instead and sent the rest of the party back to the Macedonian border. But all Mohammed's and Ameen's documents, along with the password for their money, were in the jacket.

Ameen was thrown into prison. He found 30 Syrian refugees already there: four doctors, one PhD, one MA, and all the rest university students. "It was amazing to be like that, mixed in with a group of criminals." To occupy themselves, they took turns telling the story of their first love.

They didn't get to finish all the stories, however; after ten days they were taken to the Macedonian border and released. When Ameen telephoned his brother, Mohammed did not even ask how he was. His first question was, "What is our password?" With it, they had access to money to hire another smuggler.

Three times, Ameen followed a smuggler into Serbia. Each time, after three days of walking, the police caught him.

After three times failing with the same smuggler, his brother Mohammed—who had reached Belgrade—advised him by phone to go off alone on a different route. With five new-made friends Ameen reached a small Serbian city near the border. They purchased new clothes, and then one by one went to the bus station. Ameen was the first: he bought two tickets to Belgrade, then telephoned the others to come do the same. Thus they finally reached the capital.

Once again the brothers searched for a trustworthy smuggler, and this time found one. He took them by car over the border and on to Vienna, where they caught a taxi to Munich. "The police caught us just over the border in Germany. They dealt with us as human beings. Since it was night, we asked them if we could sleep in the prison. And in the morning, we went to register."

"So," I say, "the story ended there."

"No," Mohammed answers. "The story starts there. Now we can reconstruct a future."

They are learning German, and making plans. "German," Mohammed confides in me, "is the most difficult language in the world." He has twice been in the hospital for stress. "We are always thinking of our families," he says, those in Turkey and especially those left behind in Syria, under the eye of ISIS and vulnerable to Russian bombs.

Munich.

One night in Munich I join a group from the YMCA that regularly visits a refugee camp. In a small park a block from a hastily converted office building, eleven Germans old and young bow in the dark to pray together. In Germany, the YMCA has retained its Christian heritage.

In the camp they have been given access to a preschool room, hung with hand-made paper decorations. As soon as Joachim Schmutz starts playing his guitar, refugees begin arriving: grandmothers in headscarves, little children and babies, teenagers, young men. Very shortly the room is full, and raucous with singing. "Hallelu, Hallelu, Hallelu, Hallelujah, Praise ye the Lord," we sing with hilarious enthusiasm. Most of the refugees are from Afghanistan, and have been in Germany only a short time. A few speak some English; none seems to speak any German. One of the volunteers, Simone Breischaft, learned Dari imperfectly during time in Tajikistan; she keeps asking for help with words and is eagerly assisted. She gives a little talk about God, and has volunteers read aloud verses from the Bible in their own languages. Each one is applauded.

I manage to ask a group of teenagers how they reached Germany from Afghanistan. They look at me as though I am an idiot. "We walked."

A young man who was a translator for NATO forces in Afghanistan tells me that these teenage boys have never been to school; they can't read or write. Breischaft has taught underage refugees for the last three years. She says those who have never been to school may be unable to learn to read and write German. She is doubtful how such teenagers will fare in modern Germany.

Nevertheless, she adds: "Most of the discussion about refugees is what they will do for the economy. I think as a Christian that is the wrong question. How can we say to them, I must live in comfort, so you can't?"

Beyond a doubt, Germany is crucial to the refugee crisis. So long as Germans follow Angela Merkel's lead, and so long as refugees don't become alienated and hostile, a difficult situation can be managed. Germans have great faith in their bureaucracy, that it can digest anything if given time. There has been no repeat of Cologne. No one has seen roving bands of Arab youths looking to assault German women. As to terrorist threats, with or without refugees these remain serious problems.

Osijek, Croatia: Biljana Nikolic and her husband, Djena, are Roma Christians who are aiding refugees.

But what happens if Germany closes its borders to refugees? Already passports are being checked between Munich and Salzburg, Austria, much to the annoyance of locals who have grown used to whizzing across the border.

In Austria I meet Gordy Beck, an American fluent in Farsi. For the past eight years Beck has worked with refugees through the Salzburg Baptist Church. He tells me that before last summer's surge, Austria saw 15,000 refugees a year. In 2015, 90,000 came and stayed; another 690,000 passed through on their way to Germany or Sweden. For its population size, Austria took in more refugees than Germany. Nevertheless, the huge number of refugees passing through took on a much larger prominence. The Salzburg train station became a refugee camp.

I attend a meeting of 19 Salzburg church leaders, in which they share what they are doing with refugees. A common theme is offering German lessons and sharing food and clothing. A number of churches offered Christmas parties—an opportunity to share Austrian culture while also introducing a gospel message. Churches offer help negotiating practical concerns like visits to officials.

They all want to help, and many are anxious to share their faith. Some churches report a significant interest among refugees in Bible studies. They mention that refugees openly ask questions about Christianity, and that some actively seek a new faith. Consistently, the church leaders express the belief that the situation demands a Christian response. "We can't do business as usual," says one pastor, Martin Heidenreich. "God is doing amazing things."

Bernd Wustl pastors a church of 500 in the German border town of Freilassing. He is a Teddy bear with a full white beard, who worked as an engineer for a local manufacturer before he joined fulltime pastoring at the age of 47. He says that ten years ago his church sensed God directing them to pray on the bridge that links Germany to Austria—the same crossing that Napoleon took to conquer Austria, and that Hitler followed in the Austrian Anschluss. The church held several open-air Sunday services at the bridge over the course of two years, but they never understood why they were praying.

Then in April of 2015 the refugees began to cross that bridge by the tens of thousands. Wustl's church decided to call a conference for all the local churches. "There was an unreal fear. What's happened with Germany? [At the conference] we taught people how to handle fear, so they could be freed for ministry."

The German church has two choices, Wustl tells me. "Either we wake up, open our doors and speak the gospel. Or we close doors, and forget about the German church."

The refugee crisis is a big challenge for Germany, he acknowledges.

"It will cost a lot of money. We need to find a lot of teachers. We are getting a lot of single males. I don't know how it is going to go in the future.

"If you ask me if I have a vision for the future, I say no. But I have a vision for what we should do now."

No refugee wants to get stuck in Eastern Europe or Greece. Their economies are weak; jobs are scare. Since the initial chaos of summer and early fall of 2015, these countries have either closed their borders or become refugee pipelines, adept at moving refugees through to Germany as quickly and painlessly as possible.

Croatians emphasize that they have a natural sense of empathy for the refugees, since they themselves were refugees in the 1990s, when war engulfed their country. It is a theme I hear often, from Germans who remember World War II, from Croatians and Serbians who remember the 1990s conflict, from Greeks who grew up hearing stories about hundreds of thousands of refugees from Turkey in 1922.

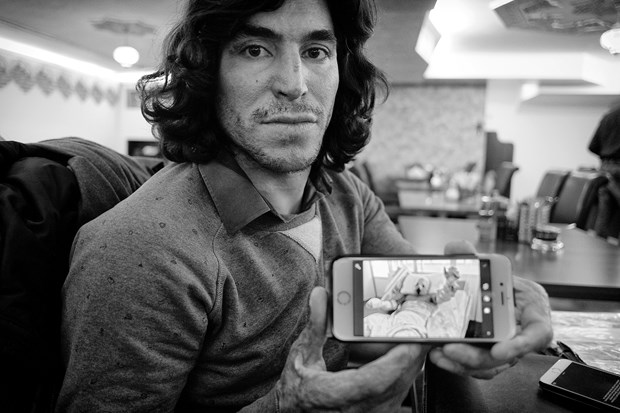

Sid, Serbia: This Syrian young man said he had to leave his city after his home was destroyed only weeks before.

When Melody Wachsmuth, an American doing PhD research in Croatia, called Djena Nikolic asking him to pick up refugees and take them to a temporary camp in Osijek, he responded eagerly. Not only did he have the war in his past, he explains that he and his wife Biljana "went through the same thing in life as Roma." Uneducated, treated like trash in most of Europe, the Roma might not be your first source of volunteers. But Djena and Biljana had become Christians, and they say that turned them from bitterness toward compassion.

On the roads around Vukovar and Osijek, refugees were everywhere, walking toward Germany. Djena began helping them find food and medical care. "When they were wet and cold, we would take off their wet clothes, and hold their babies. If they were dirty, I felt compassion. As Roma people, nobody wanted to touch us, either." Adds Biljana, "I felt compassion because I am a mother of four children, and they too are sometimes unwanted."

Djena and Biljana helped refugees every day all day from September through December, sometimes to the surprise of police who remembered them when they were beggars or scrap-collectors. Meanwhile a combination of humanitarian and church organizations, with governmental and EU oversight, gradually gained control. Elvis Dzafic, who was doing an MA in theology at the Evangelical Theological Seminary in Osijek, became a key organizer of over 200 volunteers from 22 countries working at a temporary camp in Optovac. The operation later moved to a semi-permanent camp at an army base in Slavonski Brod. The buildings are mostly containers and tents, clustered around a railroad track that carries the refugees from Sid, Serbia. Even in the dead of winter, as many as 4,000 to 5,000 refugees come each day. When Dzafic thinks of the spring, he says, "Prepare for chaos."

For now, however, there is a tense order in play. When I visit, the camp is temporarily deserted, cold and windblown. In the morning a convoy of buses left filled with refugees going west; another train is due tonight from Sid, in Serbia. Refugees usually stay in Croatia just one night. At each stop they must have their papers checked. Socks and underwear are distributed; baby food, diapers and medical aid are offered. So is an Arabic New Testament. Samaritan's Purse, Jesuit Aid, and the Red Cross are present, as is a Spanish group known as Remar. Dzafic heads Croatian Baptist Aid, an umbrella group created to coordinate the work of making refugees welcome. Whereas volunteers in Germany and Austria are mainly natives, he has volunteers from many countries, including the US. Few will stay long. Dzafic is exhausted. He wonders whether there will be enough help when the numbers go up again in the spring.

Across the border in Sid I meet Goran Stupac, a Serbian working for World Vision. "When I first saw the refugees, there was a kid my own son's age riding on his father's shoulders, dirty, with a runny nose, his clothes falling off him. I started crying. I couldn't cope with it."

In September of last year, Stupac says, World Vision helped 100,000 refugees as they went through Serbia. Since Hungary closed its borders and the stream of refugees narrowed to Croatia, they've seen 600,000.

The Sid stop is located at an abandoned hotel beside the freeway, behind which army tents have been erected for emergency shelter. World Vision has a refurbished room where mothers with small children can come and find relief. Children's drawings are tacked on the wall. A girl who signs herself Mariam pictures herself leaving home (absurdly small, on a field of bright green), clutching a small sack in her hand, the size of a purse. Many pictures include flags, symbols of a surrendered identity: Kurdish, Afghani, Syrian, Iraqi. What children draw flags? One shows the Afghan flag and an EU flag with a heart between them; over the heart is a Greek flag.

In the early afternoon, buses arrive packed with refugees, including many families with small children. They are dressed in warm clothes for the bleak, gray weather. Their eyes are tired. They get off the buses to walk about aimlessly in the mud.

I greet a tall, good-looking young man from Afghanistan, Mohammed Rafi. He says he is a university-trained computer science engineer from Herat. His father owns a construction company—he says they did projects for World Vision—but with the Taliban surrounding the city there is no way to make a living. He left alone, with his father's blessing.

Like others, he came through Turkey. And how, I ask, was his trip to Greece? Mohammed falters. "The boat I was on, 24 people drowned." For a time, he cannot speak, and neither can I. Later he takes a paper out of an inside pocket of his jacket, with the printed names of the 24 who died. He says it happened just eight days before.

I talk with a cluster of young men, two Syrians and two Iraqis. "I am willing to do any job," one of them volunteers. One is a high school graduate, another is in his first year of college, a third is in his second year studying electronics. They too look exhausted; they say they don't sleep well on the bus. One of the Iraqis takes out his phone to show me a picture of his home, leveled by artillery on October 15.

Athens: At Bethel, a retreat center and hostel in Athens run by Greek Scripture Union, Syrian and Yemeni refugees have been invited for excercise, food, and rest before their journey toward Germany begins. This woman is in a wheelchair after being injured by a car bomb in Syria.

One of the Syrians turns angry as he reflects on their trip across the water. He has unusually luminous hazel-colored eyes that turn on me fiercely. "Why doesn't the Turkish government help us cross?" he asks. "The boat just before mine, 40 people were killed. It's very dangerous. Turkey doesn't let us live there, but they don't want us to leave. What do they want? To kill us? It's so dangerous!"

From the abandoned freeway hotel, the refugees will be bused to a deserted train siding on the outskirts of Sid itself. There are only a few refugees present when we arrive there, but we find three Moroccans who have been detained: Mohammed Zein, 21, Khaled Buzianai, 24, and Ahmed Khalil, 24. They flew to Turkey from Morocco and found a smuggler's boat to Greece. They say they have felt no fear at any point on the way. "We got papers here and they said we have to wait."

I ask why they left Morocco. They say they are looking for jobs.

"There are no jobs in Morocco?" I ask.

"There are jobs in Morocco, but they don't pay well."

Overwhelmed by those fleeing war or persecution, Europe has no interest in accepting such economic migrants. I expect they will be sent back, as will hundreds of thousands of others whose applications for asylum are turned down. How exactly that will be done, and when, remains a mystery.

Finally, Greece. Our first day in Athens we join a group of Syrian and Yemeni refugees hosted by a group of Texans from WoodsEdge Community Church, volunteers with Operation Mobilization. The gathering takes place at Bethel, a retreat center and hostel run by the Greek Scripture Union. There is food, volleyball, ping pong. It is an extraordinary and happy mix of Greeks, Americans, Syrians and Yemenis.

One of the Syrians is Mahmoud Khalifa, an electrical engineer, who left Aleppo three months earlier with his wife and three severely retarded children, ages 20 to 17. They can't walk, can't hear, and can't control their bowels. In Aleppo, Khalifa couldn't get medical care for the children; he couldn't even leave the house without fearing for his life. So finally he set off for Turkey; he says he walked many, many miles with painfully arthritic joints, pushing or carrying his children. After two weeks in Turkey, they boarded a small fishing boat. He was terrified that his children, who sometimes flail about in alarm, would be refused passage or thrown out of the boat. But the passengers, though packed tightly onto the badly overloaded boat, remained kind even when the overburdened engine quit and water started coming into the boat. Rescued by the Greek military, they came to Athens, registered for asylum, and—after a two-month wait—have been accepted by the Netherlands. Khalifa is a very happy man. "I'm living for my children," he tells me.

Next day I go to the Elliniko refugee camp, located in some abandoned facilities from the 2004 Olympics. These buildings—a small stadium and a basketball arena—were sited on miles of runway and tarmac from the old Athens airport. Many of the refugees at Elliniko are those who aren't going to be granted asylum. In an improvised dormitory I meet a Libyan, a Western Saharan, and three Somalis. All five come from war-torn regions. But word has it that Germany is currently welcoming only those from Iraq, Syria, and Afghanistan.

Ali, a Somali, tells me that he is a certified school teacher in Somalia. He has been to Egypt, Sudan, and Turkey looking for a place to live. "I have no hope," he says.

From Elliniko I go to the port, where newly arrived refugees fill a large hall ordinarily intended for passengers on massive ferries to the Greek islands. Blankets and sleeping bags are spread on the concrete floor; people rest or talk; young men cluster around outlets where they can recharge their phones; children play games with a ball. I fall into conversation with a group of seven young Hazara men from Afghanistan. They come from different cities but found each other in transit; they say they are the only Hazara out of the hundreds in this hall.

Ahmad Atib shows me an identity card from his job at the Afghanistan International Bank in Kabul. He has photographs of himself and bank colleagues posed in dark suits. He left, with his younger brother, because of death threats from the Taliban. "At first we didn't take it too seriously. Then my father received an official email from the American embassy, warning that his organization (International Assistance Mission) was targeted." His father, disabled with polio, sent his two sons on a route that led through Pakistan, Iran, Iraq, Turkey, and Greece. Atib says that he has worn out one pair of running shoes; fortunately, his smuggler told him to bring two.

Atib left with his wife of eight months, but they lost each other while crossing the Iraq border. He and his brother had gone ahead in the dark; a group of women and children, moving more slowly, were caught by border guards. Atib has been unable to contact his wife; he has no idea where she is, nor do his relatives in Afghanistan. He has posted a message on the internet, hoping that she will eventually read it and respond.

Crossing mountains in the snow, sometimes wading through chest-deep, icy water, he reached a point where he felt he should just give up. On his long journey he had multiple encounters with border police. "I feel allergic to police," he tells me. "For 20 days I lived with fear." Greece is another world. "Now I am safe and secure. Now I can sleep."

The last day of our journey we reach the Greek island of Lesbos, where many refugees first encounter Europe. The wind is blowing hard and cold; not a thousand feet above us the hills are stained with snow. Along the northern shore, closest to Turkey, the sea is a deep luminous green, and farther out are whitecaps. There should be no boats on the water today; I pray there are none. Turkey is astonishingly close across the wind-whipped sea . We can see buildings clearly. It is only a few miles. A speedboat towing water skiers could cross shore to shore in 10 minutes.

A rough dirt road follows the narrow, rocky beach. To my eye it looks like there are shiny black rocks at the surf line, but when I get out of the car and walk down to the water I see that they are the torn and twisted remains of inflatable rubber boats.

Lesbos is a big island—it takes us an hour's drive to get from its capital of Mytilene (where the apostle Paul stopped by) to the beaches where most of the refugees arrive. The island is undeveloped and uncrowded: terraces of olive trees, red-tiled stone villages, the soft shadows of dun hills and mountains. In the summer, vacationers flood here. Just now Lesbos is crowded with volunteers from many nations; they are doing much of the actual work helping the refugees. Whereas in Germany volunteers offer only what is above and beyond the essentials, here volunteers man practically everything.

The first stage is beach-side rescue: volunteers on the water, scanning the horizon for boats, ready to rescue any that founder. A doctor tells me that the primary problems she sees are hypothermia and panic.

Stage 2 consists of relatively small camps set near the beach: a cluster of white tents offering a warm place, dry clothes, food and water. Here refugees are given a quick assessment, and a ticket for the bus to Stage 3. Ben Cook, a fit young African American in a Peterbilt watch cap and a fireman's jacket, oversees the volunteers at one Stage 2 camp; he came as part of Youth with a Mission and has stayed on with Operation Mobilization. "We're all believers in this camp," he says. "We can't preach. Our goal is to make them feel like human beings." The work is overseen by the UNHCR and the Greek government, but much of the manpower comes from volunteer groups, a lot of whom are Christians.

There are two Stage 3 camps, bigger operations that can handle thousands of people, offering very simple (and crowded) sleeping rooms, meals, showers, and the government registration that enables refugees to move forward. Refugees who choose to apply for asylum in Greece will be supported while they wait for an answer and then—if the answer is favorable—an assignment to a receiving country. Most refugees simply want to go on to Germany, and Greek documents enable them to do that—to Belgrade, to Sid, to Croatia, and all the way to Austria and Germany.

Mytilene, a city of 30,000, was overwhelmed last summer by 35,000 refugees, who blocked roads with their sleeping bags and blankets and tents. Some residents could not even reach their homes.

Hannah Gaganis, a Canadian who moved to the island with her university-professor husband, went to their 30-member evangelical church praying, "God help us!" At first, she admits, she felt overwhelmed: "I had a fear of rape. I felt threatened, even though I understood the refugees' anger. They were making it difficult for us to live. There were fights, riots, there was a terrible stench."

Yet "the reaction was surprisingly good," lay pastor and communications professor Philemon Bantimaroudis says. "I would have expected hostility. This is an island society. After living here 15 years I'm still a foreigner." Perhaps because so many had memories of being refugees themselves, local people reacted compassionately. They offered food and water, especially to refugees who were walking 30 or more miles in terrible heat from the beaches to the port to get a ferry for the all-night voyage to Athens. By late August, a huge number of NGOs had begun to arrive, and the situation normalized. Now refugees spend only one or two days on Lesbos before they catch the ferry to Athens.

Lesbos: A camp for Afghan refugees.

Gaganis says that the church had been involved with refugees for years, even if the numbers were laughably small compared to now. "One hundred and fifty people! What are we going to do!"

When the flood began, a woman from Doctors Without Borders asked the church to pack 5,000 food bags. They began distributing them without any experience in how to do so, and nearly caused a riot. "We were mobbed."

Soon, though, they learned how to distribute food and water more practically. The church would pack lunches, and the church kids—on summer vacation—loved to pitch in. "It was just so much fun."

"What is phenomenal," she adds, "Is that tomorrow at our Sunday service there will be 30 Greeks and 50 Americans. We have been an isolated church. Apparently God has an unusual way of working with us."

When the weather turned cold, Gaganis began to think of mothers with small children. The church rented a space where they could come to rest and get warm. Now Gaganis spends much of every day there, offering shelter.

"It was so blazingly obvious to do this for refugees," she says. "It's easy."

Bantimaroudis adds, "You can't ignore it. Any church would have done it."

"The next step," says Gaganis, "the harder step, would be to do this for Greek society."

Now that I have reached the end of our journey, I find I don't know how to summarize it. It is like witnessing an earthquake or a tornado: there is not much analysis to be done, just description. These are the people. These are their stories. These are the responses, however feeble. I don't know what comes next. Nobody does. In our 2½ weeks, Gary and I talked to many, many people, but not one ventured to describe a comprehensive solution.

(On March 18, several weeks after we returned to the US, Turkey and the EU announced an agreement under which refugees and migrants arriving on the Greek islands or the mainland will be quickly sent back to Turkey unless they qualify for asylum. There is a great deal of uncertainty about how the agreement will be implemented, and whether it will stand up to challenges under international law.)

We drive up to the dumping ground for life vests. I have seen pictures of it on YouTube, but I am not really prepared. High on a barren hill is a huge swale of shocking orange. It is a lumpy mountain fifty yards across, ten to twenty feet deep. The vests' fluorescent orange blazes from the duns and sages of the Mediterranean brush.

What hits me hard is the individuality of these vests. They are like the piles of shoes or the costume jewelry preserved from Holocaust death camps, only in this case they are mementos of survival, not death. Somebody wore each of these like a second skin. They left their scent, and perhaps a little blood. They counted on these vests to preserve their life as they crossed deep water.

Now they have left them behind, cast off like misshapen and bulky clothes. The immediate danger has passed. Some didn't survive the journey, but most of the people who wore these vests are somewhere in Germany, beginning a new life.

Tim Stafford is general editor for God's Justice: the Holy Bible (Zondervan). He is currently at work on a novel set in a gospel mission.

Copyright © 2016 by the author or Christianity Today/Books & Culture magazine.

Click here for reprint information on Books & Culture.

No comments

See all comments

*