Philip Yancey

Darkness and Light in India

Paradoxes abound.The cows, always the cows, hundreds of them, thousands of them. They stand in a pack blocking traffic, take naps in the middle of a busy highway, walk unmolested through a fruit stand, devour the grass and flowers in a public park. Somehow the snarling motorcycles, motorized rickshaws, trucks, and automobiles thread their way through the bovine obstacle course—a good thing, for woe to the Indian driver who injures a sacred cow.

India assaults the senses. Vehicle horns beep out a percussive background rhythm to life in cities and villages both. Women in bright-colored saris squat along the roadside, cutting the grass by hand with knives. An elephant wanders by, gaudily painted for a Hindu festival. A motorcycle zooms past: a young boy no older than two stands on the seat grasping the handlebars while behind him his six-year brother is sandwiched between the father, who is driving, and the mother, who is sitting side-saddle and holding an infant fresh from the hospital (none of them wear helmets). A funeral procession marches down a side street to the beat of a drum, its mourners lighting firecrackers to scare devils from the cemetery.

Some of our best doctors and software engineers have emigrated from India, and when my computer locks up, chances are I'll talk to a support person based there. Yet in this paradoxical nation twice as many people have access to cell phones as to toilets and running water. I visited a high-tech hospital that outsources laundry service to women who use big, heavy irons that flip open to reveal charcoal as the source of their heat. I asked my Indian host about the colorful plastic bags hanging like oversized Christmas ornaments from some banyan trees. "Oh, they contain the placentas of cows," he said, which explained the ever-present odor. "Villagers believe the practice will make their birthing cows more fertile and produce more milk."

Paradoxes abound. A land where temples display carvings of shockingly explicit sexual acts, and the home of Kama Sutra, houses a Bollywood movie industry that rarely portrays anything beyond a demure kiss. Divorce is rare, though a majority of marriages are still arranged by parents, not the product of romance. The caste system has supposedly ended, but everyone's identity card specifies his or her caste, and matrimonial ads in the daily papers stipulate the caste of prospective suitors; lower castes need not apply. While Westerners value a bronze, tanned look, Indians advertise for applicants with "wheatish skin."

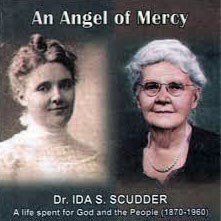

I made my fourth trip to this land of endless fascination in August. I'd been asked to give the Ida Scudder Humanitarian Oration (a fancy word for a speech) at the Christian Medical College in Vellore in honor of Dr. Paul Brand, with whom I wrote three books.

The Healing Place

CMC Vellore, as it's known, has a storied history. In the early 1800s Dr. John Scudder of New Jersey became the first medical missionary to India. Seven of his sons followed in his footsteps, likewise serving as missionary doctors in India. Growing up in such a single-focused family, granddaughter Ida Scudder wanted nothing more than to find a non-medical career, marry, and settle in the U.S. A visit to care for her ailing mother back in India changed her plans.

Late one night during that visit a Hindu Brahmin knocked on the door and asked for help; his 14-year-old wife was in great distress trying to deliver a child. Ida said she knew nothing about medicine but would notify her father. The man shook his head, responded "Our religion does not permit a man to even look at my wife's face," and went away crestfallen. That same evening a Muslim and then another Hindu came with an identical request of help for their wives in childbirth. Each time Ida offered the same solution and each time the men turned it down, saying it was better that their wives die than be seen by a man. The next day all three young women were taken away in coffins.

Convinced that extraordinary night was a sign from God, Ida returned to the U.S. and studied medicine at Cornell, becoming its first female medical graduate. She went on to found a small clinic in Vellore in 1902 and then opened a nursing school for women and ultimately a medical school to train female physicians. At the time, female patients in India faced a Catch-22 situation: although custom prevented male doctors from treating them, few medical schools in India accepted women. Skeptics warned Dr. Scudder that she might get two or three female applicants; 151 women applied to the medical school. Not until thirty years later did the school begin accepting male applicants.

Early view of CMC Vellore

Today CMC Vellore is ranked the number one private hospital in India and one of the most prestigious medical schools in Asia. It has 8500 employees and treats a million patients a year. Recognizing the limited resources of many villagers, the hospital offers three levels of care. The highest level compares to high-tech hospitals in the West. The second level offers quality care but houses patients in village-type accommodations, with relatives providing meals and bedside attention. (At this level a normal childbirth delivery costs only $60, increasing to $100 if a Caesarian section is required.) And community health workers travel to nearby villages in vans to provide free nursing and physician services.

CMC nurses on a village visit

In contrast to many hospitals in the U.S. that still bear words like Baptist, Presbyterian, or Good Shepherd in their names, CMC Vellore retains a strong Christian emphasis. Posters with Bible verses decorate the hallways, doctors and nurses offer to pray with patients, and the hospital funds a large chaplaincy corps. The medical college selects 100 students a year from a pool of 30,000 applicants, giving strong precedence to those who agree to a two-year service with their sponsoring churches and missions.

While working at this institution, the British surgeon Dr. Paul Brand began his pioneering work with leprosy patients. Much as Ida Scudder had learned about women patients, Dr. Brand found that the doors of traditional medicine were closed to those with leprosy. The disease was so feared that hospitals dared not admit them. Eventually he helped establish a leprosy hospital outside the town of Vellore, which became a world-renowned center for leprosy research and treatment.

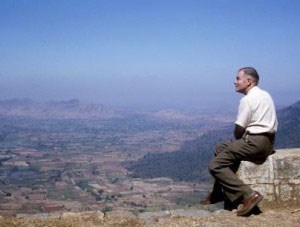

No one has affected me more than Dr. Paul Brand. He was a brilliant scientist, an avid environmentalist, an astute theologian, and a compassionate physician. In short, Dr. Brand lived life to the full, and his deep faith permeated everything he did. I met him at a time when I was recovering from an unhealthy church and wrestling with doubts and questions. My first book, Where Is God When It Hurts, came directly out of our conversations on pain and suffering. For nearly a decade I worked to present his life and ideas in the books Fearfully and Wonderfully Made, In His Image, and The Gift of Pain. The first two books are based on chapel talks Dr. Brand delivered at CMC Vellore.

Speaking at Dr. Brand's funeral in 2003, I said that we had an unusual exchange. While I was giving words to his faith, he gave faith to my words. Yes, he helped me with some of the intellectual issues. More importantly, though, he lived out the principle articulated by Irenaeus in the second century: "The glory of God is a person fully alive."

As a scientist, humanitarian, adventurer, and explorer of the natural world, Paul Brand was fully alive. He spent his best working years among some of the most abused and neglected people on the planet, leprosy patients from the Untouchable caste, yet I have never met anyone with a deeper sense of gratitude for God's good world. I felt privileged to honor him in the Oration at Vellore, which was attended by three of his six children as well as two grandchildren. Dr. Brand's widow Margaret, a physician who specialized in treating the ophthalmic conditions of leprosy, was unable to make the trip.

The cherished memory of Paul Brand is evident at the hospital: photos on the wall, a hand surgery and rehabilitation center named for him, a building dedicated by him. Both Brands are revered in the best sense of the word: not as a form of hero-worship, but as models of whole-person medicine, with an emphasis on the spiritual core. CMC Vellore works hard to communicate their legacy to future generations.

The Suffering Place

Besides the visit to Vellore, Janet and I made two other stops. We first landed in Mumbai (Bombay), scene of haunting memories from 2008. On the final leg of a book tour that fall, I was scheduled to speak downtown when a murderous assault by Pakistani terrorists made that impossible. Using bombs and AK-47s, two dozen gunmen attacked ten different sites, most notably the Taj Mahal Hotel, killing 164 and wounding at least 308. We were staying at the home of Dr. Stephen Alfred, safely away from the scene of the tragedy—providentially, since in every other city we had stayed in the kind of tourist hotels targeted by the attackers.

Dr. Alfred has since built a modern, eight-story hospital equipped with state-of-the-art technology for procedures such as radiation oncology, dialysis, and MRI and CT scans. The staff takes seriously the motto, "Not to be served, but to serve," plowing back the profits from paying patients to provide treatment for the 50 percent of patients who could not otherwise afford care. Bethany Hospital turned over its former building to JSK, a partner ministry for those affected by HIV/AIDS (CLICK for more about that visit) . In addition to providing in-patient care, this program sends staff and volunteers into homes in order to monitor the antiretroviral medicines and help families cope with the devastating disease.

Floral welcome in Damoh

We also visited the village of Damoh in central India. Like so many missions, the work of Central India Christian Mission expanded to meet the local needs. First the Indian founders, who had studied in the U.S. and developed a donor base, began caring for children abandoned by their parents; then they began assuring women with unwanted pregnancies that if they chose against abortion the mission would care for their babies. That led to a children's home, then a school, a youth center, a vocational training center, a nursing school, and a small hospital.

The mission also sponsors pastors and evangelists throughout India. Several hundred of them gathered for a one-day seminar that I taught. In the final hour before we left to head back to the U.S., the director arranged for interviews with some of the attendees who had been victims of a terror campaign by Hindu fanatics in the state of Orissa (now known as Odisha). In August and September of 2008, rampaging mobs burned around 6000 houses belonging to Christians, killing 400 and displacing 50,000 Christians, who were forced to flee to refugee camps. Even now, six years later, thousands of families in Orissa remain homeless. The mission has established a center of refuge for such trauma victims.

I knew of the earlier murder of Graham Stuart Staines, an Australian missionary who worked with leprosy patients. Along with his two sons Philip (aged 10) and Timothy (aged 6), Staines was burned to death by an ax-wielding gang while sleeping in his station wagon. His widow pleaded for mercy for the perpetrators and stayed five more years until the Staines Memorial Leprosy Hospital was completed. I had also forced myself to watch YouTube videos of mobs beating to death helpless Christians and chasing stripped women through the streets to beat them with clubs. I had read accounts of nuns raped and pastors burned in their churches. But nothing prepared me for the final meeting when I heard firsthand accounts of that dark time.

Orissa: One of 400 churches burned

One man with the saddest expression I have ever seen recounted those days when Hindu fanatics offered a 10,000-Rupee reward for anyone who killed a preacher and 5,000 Rupees for anyone who destroyed a church. They burst into the home of one of the church members, gang-raped a young girl as her parents were forced to watch, then burned the parents alive before the children's eyes. Christians had to pass five tests to avoid martyrdom: shave their heads, drink cow urine and eat dung, pay a 10,000-Rupee temple tax, wear a prominent red mark on their heads, and present a sword dripping in Christian blood.

"Six hundred homes were burned in my village," the man said in a flat monotone, not lifting his head. "I watched them tie up my father, pour kerosene on him and burn him alive. We ran into the mountains to join the other refugees. It was the hardest thing I have ever done, leaving my father like that."

A small, trembling woman wearing a turquoise sari could hardly speak through her sobs as she recalled her ordeal. "I was a pastor's wife. A gang of a thousand men burned our entire colony. Seven of them took turns raping me in front of my husband. And then as they held me down they chopped my husband into pieces. They poured kerosene over me, lit a match, and left. Somehow I managed to crawl to a bucket of water." She showed the scars on her head and the skin grafts and missing fingers on her hands.

Four witnesses told their stories in graphic detail. They spoke through two interpreters in a tribal language that had to be translated first into Hindi, and then English. All four had traveled 24 hours by train to attend the seminar. Choking back tears, a pastor told of a teenage girl in his church who had been forced to watch her parents killed, and then was raped 42 times before being left for dead, with burns over 60 percent of her body. "I am still a pastor," he said. "I have been privileged to introduce 6000 people to Jesus. But every day when I kiss my wife goodbye I tell her I may never see her again."

A 12-year-old burned in riots

I left India with furiously mixed emotions. I was inspired by the dedication of Christians who care for AIDS patients, provide free health care for the poor, and help reconstruct the bodies and lives of leprosy patients. Yet I will never forget the horrifying accounts of suffering I heard from the lips of these four witnesses. It is one thing to read about such events in newspapers or on the Internet and quite another to sit in the same room as the people who endured them, their physical and psychological scars still appallingly evident.

"In him was life, and that life was the light of all mankind," wrote John in the prologue to his Gospel. "The light shines in the darkness, and the darkness has not overcome it." On my trip to India I saw clear evidence of both the darkness and the light.

We left Damoh with heavy hearts. And when we arrived in the Delhi airport later that same day, I picked up an English-language paper and read about the ongoing atrocities against Christians in Iraq and Syria. The U.S. was rightly giving emergency assistance to 40,000 Yazidi refugees whom ISIS had driven from their homes under the threat of genocide. But a few weeks before, ISIS had displaced more than 100,000 Christians from their homes and driven them into the desert—with no such emergency response.

Not only in India, but in many parts of the world Christians are in the line of fire. As Pope Francis stated earlier this summer, Christians suffer perhaps the largest share of religious persecution in the world today:

It causes me great pain to know that Christians in the world submit to the greatest amount of such discrimination. Persecution against Christians today is actually worse than in the first centuries of the Church, and there are more Christian martyrs today than in that era. This is happening more than 1700 years after the edict of Constantine, which gave Christians the freedom to publicly profess their faith.

I went away mindful of a principle Dr. Paul Brand once taught me—he who identified leprosy as a disease of painlessness: "A healthy body is one that feels the pain of the weakest part." The same principle applies to the Body of Christ. May we never forget those who suffer for the light in a darkening world.

Philip Yancey is the author of many books, including Soul Survivor: How Thirteen Unlikely Mentors Helped My Faith Survive the Church. This essay was posted on his blog site in August.

Copyright © 2014 Books & Culture. Click for reprint information.

No comments

See all comments

*