Philip Yancey

Farewell to the Golden Age

How publishing has changed.

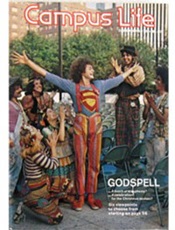

I have lived through the golden age of publishing, first with magazines and then with books. I began my career at Campus Life in 1971, and in ten years saw our circulation leap from 50,000 to 250,000. Like many magazines, Campus Life eventually bit the dust as advertising dollars migrated to flashier (and cheaper) online sources and consumers no longer responded to direct mail offers and renewal letters.

For almost four decades (yikes!) I've worked as a freelance writer, feeling enormously blessed to make a good living by writing about issues of faith that I would want to explore even if no one bought my books. Every year my royalties go down, though with more than 20 books in print I can still pay bills and find publishers willing to sponsor new books.

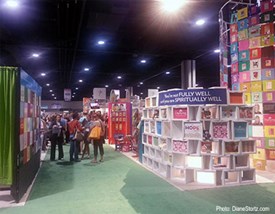

The changes in publishing, especially Christian publishing, stood out sharply to me when I stopped in at the largest annual Christian book convention in June. At one time 15,000 attended that trade show, a convention so large that only a handful of cities could accommodate it. Now less than 4,000 attend, and in Atlanta it occupied a corner of the huge convention center. A couple hundred delegates attended a luncheon in which I participated on a panel with Ravi Zacharias and Ryan Dobson; ten years ago the same luncheon would have filled a thousand-seat banquet hall. Though name authors had book signings, the only lines I saw were for two stars of Duck Dynasty.

Book publishing is going through massive changes. Almost every month bookstore sales fall below the total from last year … and the year before. Of the 5,000 Christian bookstores in the U.S. open in the 1970s, barely half that number have survived. What happened?

In truth, many Christian bookstores were "mom and pop" stores run more out of a sense of ministry than business acumen. Managers stocked too many titles, knew little about marketing, and stayed in business mainly because every so often a mega-seller like The Purpose Driven Life or the Left Behind series would come along to rescue their bottom line. In the early 1990s chain stores such as Walmart, Costco, and Sam's Club started picking off these bestsellers and general bookstores like Borders (now defunct) and Barnes & Noble greatly expanded their religion departments. Then came Amazon.com, offering deep discounts to siphon off the steady sales that kept small bookstores afloat.

There was a cost to the industry, of course. No longer would shoppers browse the shelves, pick up books to scan the contents, and walk out with five books when they had intended to buy just one. Now they ordered the one they wanted online, untempted by new books they did not even know existed. Scores of college and seminary bookstores closed as students ordered the required books online, forfeiting the ability to browse among unassigned books that also might interest them.

Christian bookstores adapted by expanding their product line. Many Christian bookstores today realize less than 30 percent of their profits on books. Instead they stock Precious Moments statues, greeting cards, toys, games, Thomas Kinkade prints, and religious kitsch. People still like to finger gift items before they buy.

In the past five years the digital revolution has introduced a whole new challenge to the publishing industry, much like its impact on music and movies. Until last year e-books were rising at double-digit rates. For publishers and also authors (the "plankton" of the publishing food chain), this has meant a drastic reduction in income. Say an author signs a contract to receive a 10 percent royalty on each book sold. In the old days he or she would receive $2.50 on a $25 hardback book. Now Amazon offers the book electronically for $9.99 and often offers specials of $2.99. For the same amount of work, the author may receive half or even 10 percent as much as from "dead tree" publishing.

Last year publishers in the U.S. took in $15 billion in income from all sources. E-books represented one-fourth of the sales volume but only 10 percent of the revenue, due to their lower prices.

For a first-time author, these are the best of times and the worst of times. Thanks to advances in self-publishing, anyone can get a book in print—as long as you're willing to bear the costs of production, marketing, and sales that used to be absorbed by publishers. Brick-and-mortar bookstores generally won't stock your book, so you have to find other ways to get the word out. Good luck.

You can lower the cost by publishing in electronic format only, in which case you'll need even more luck. The best-selling author Tony Horwitz (Confederates in the Attic, Midnight Rising: John Brown and the Raid that Sparked the Civil War) recently wrote in the New York Times about his experience with electronic publishing. He was delighted to find that his instant book on the Keystone pipeline, Boom, had landed in the Amazon Top 25 list of all digital titles—only to learn that he had sold a mere 800 copies.

I had an enlightening experience with e-books in 2013. In April I finished the book The Question That Never Goes Away, based on my visits to three places of great tragedy. My traditional publisher wanted at least nine months lead time to publish it, the typical schedule for a new book, yet new tragedies such as the Boston Marathon bombings, tornadoes, and school shootings were occurring almost weekly, the very situations my book addressed. So I signed on for an Amazon-exclusive program to publish an e-book for 90 days before the hard copy book came out. Leaning on my friends for email lists, I managed to sell about 3,000 copies. On September 11 and Thanksgiving weekend I offered free downloads and 40,000 people downloaded the book! The moral of the story, as many have learned: things can quickly go viral on the Internet but it's a tough place to generate income.

Trust me, I have no sour grapes. My main motive in writing the book was to bring perspective and comfort to people going through hard times, and if 40,000 people got it free, all the better. As I say, I have made a good living from writing and would probably keep doing it even if all my books were free. I do worry, though, about new authors who don't have a backlist to depend on. As readers are trained to pay less (or nothing) for books, how can authors survive?

Last year Amazon sold more e-books than hard copy books, and some experts predict that by 2016 e-books will represent one-half of all books sold. (E-book sales have recently cooled, however, and that prognostication now seems unlikely.) Half of U.S. adults now own an e-reader or tablet computer, and there appears to be a generational divide. According to the Financial Times, 52 percent of 8- to 16-year-olds prefer reading on screen, with just 32 percent preferring print.

Certainly, e-books offer significant advantages. They are amazingly portable, for one thing. Logos Bible Software offers a package of 2,500 books that fit comfortably on a laptop computer and are instantly available with a few clicks. Someone kindly gave me a Kindle Paperwhite reader, and I find it ideal for reading books on a long trip without straining my arm or briefcase.

We still don't know the long-term effects of reading e-books vs. traditional hard copy books. Some studies show that people read slower on dedicated e-readers, and those who use tablets or computers or iPhones have a different reading experience, being constantly distracted by text messages, emails, Facebook, and other interruptions. Nicholas Carr's The Shallows: What the Internet Is Doing to Our Brains explores the changes in brain function that may result. Hyperlinked, multi-tasking readers do not have the same "deep reading" experience, and are less likely to store what they read in long-term memory.

In short, we face a revolution in reading not unlike the one Gutenberg introduced almost 700 years ago. Nowadays authors are coached on "building your brand" more than on improving their writing. Publishers care more about website stats and Twitter followers than the quality of an author's work.

Frankly, I'm glad I'm as old as I am. It's been fun living through publishing's golden age. I'll happily stick with the "deep reading" experience. Nothing gives me more satisfaction than browsing through the books in my office. They're my friends—marked up, dog-eared, highlighted, a kind of spiritual and intellectual journal—in a way that my Kindle reader will never be.

Philip Yancey is the author of many books, including Soul Survivor: How Thirteen Unlikely Mentors Helped My Faith Survive the Church. This essay was posted on his blog site on July 6, 2014.

Copyright © 2014 Books & Culture. Click for reprint information.

Displaying 0–0 of 0 comments.

Displaying 0–0 of 0 comments.

*